Introduction

How do you explain when others are able to achieve things that seem to defy all the odds and assumptions? For example in Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card, why was Ender Wiggin very effective as a leader in one of the greatest battles of science fiction history (Card, 1977)? He certainly was not the most fearless person, nor was he the most merciful, and Mazer Rackham was clearly more experienced than Ender. So why bet on Ender to lead? Why was Alexander the Great such a successful leader at a very young age? At 16, Alexander was appointed reagent on a campaign against Byzantinum because of the absence of his father King Philip (Borza, 2007) Before turning 20 Alexander became king, and year after year he ruthlessly crushed his competition on the Greek mainland (Borza, 2007).And yet, Alexander was just like every other Greek leader. He had the same access to the same talented soldiers, the same consultants and advisors. So why bet on Alexander to lead? Why did Joan of Arc possess the audacity to drive the English out of France (Freeman, 2008)? She was not the only person to suffer under the British monarchy, and there were certainly more experienced and more qualified individuals to revolt against the English. So why bet on Joan to lead? Ender Wiggin, Alexander the Great, and Joan of Arc, are successful leaders because they believe in the importance of establishing a strong reputation, and are aware that military triumphs will motivate oppressed citizens.

Ender and Alexander the Great

Ender and Alexander both gained a lot of power because of their ability to establish a firm reputation among peers. In ground school Ender is taunted and bullied by Stilson every day (Card, 1977). When Ender gets his monitor removed, Stilson’s gang surrounds Ender, and Ender realizes that he needs to fight Stilson to prevent bullying once and for all (Card, 1977). After brutally hospitalizing Stilson, Ender sends a message to anyone that wants to pick a fight with him. This helped Ender establish a reputation amongst his peers for being fearless, and helped him get promoted to battle school. Alexander the Great’s also realized the importance of establishing a good reputation among peers. Contrary to what Alexander was taught by Aristotle, he fraternized with Asian administrators (Borza, 2007) Asians were considered barbarians, and instead of establishing a “master to slave” relationship (Borza, 2007) Alexander treated them like civilized people. Alexander’s disregard of Greek politics helped him collect allies from the east, which increased soldier talent and diversity in his army. Both Ender and Alexander understood the importance of building a respectable reputation which helped them achieve extraordinary accomplishments.

Ender and Joan of Arc

Ender Wiggin can also be compared to Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) because both experienced military triumphs at a very young age that inspired civilians. Throughout Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card leads the reader to a major plot scene concerning the Third Invasion. After defeating the 10-billion-strong bugger enemy, Ender’s battle colleagues leave Eros and return to earth (Card, 1977). On Earth, Ender’s friends praise his military tactics, and inform civilians about their victory (Card, 1977). Colonists that visit Eros, are so delighted to meet Ender that they admit naming their child after Ender Wiggin (Card, 1977). Whether Ender’s intended to become a role model or not, he certainly inspired a generation. Similarly, in Joan of Arc’s short lifespan, she convinced the Dauphin to supply her with troops which she used to end the siege of Orleans (Freeman, 2008) Joan of Arc’s brave accomplishments in battle were lauded by the French public. She was able to motivate France to combat the English. The comparison between Ender Wiggin, and Joan of Arc shows the effect of impressive military feats. With remarkable military accomplishments, Ender and Joan of Arc were able to instill zest in a community oppressed by powerful monarchy.

The Golden Circle

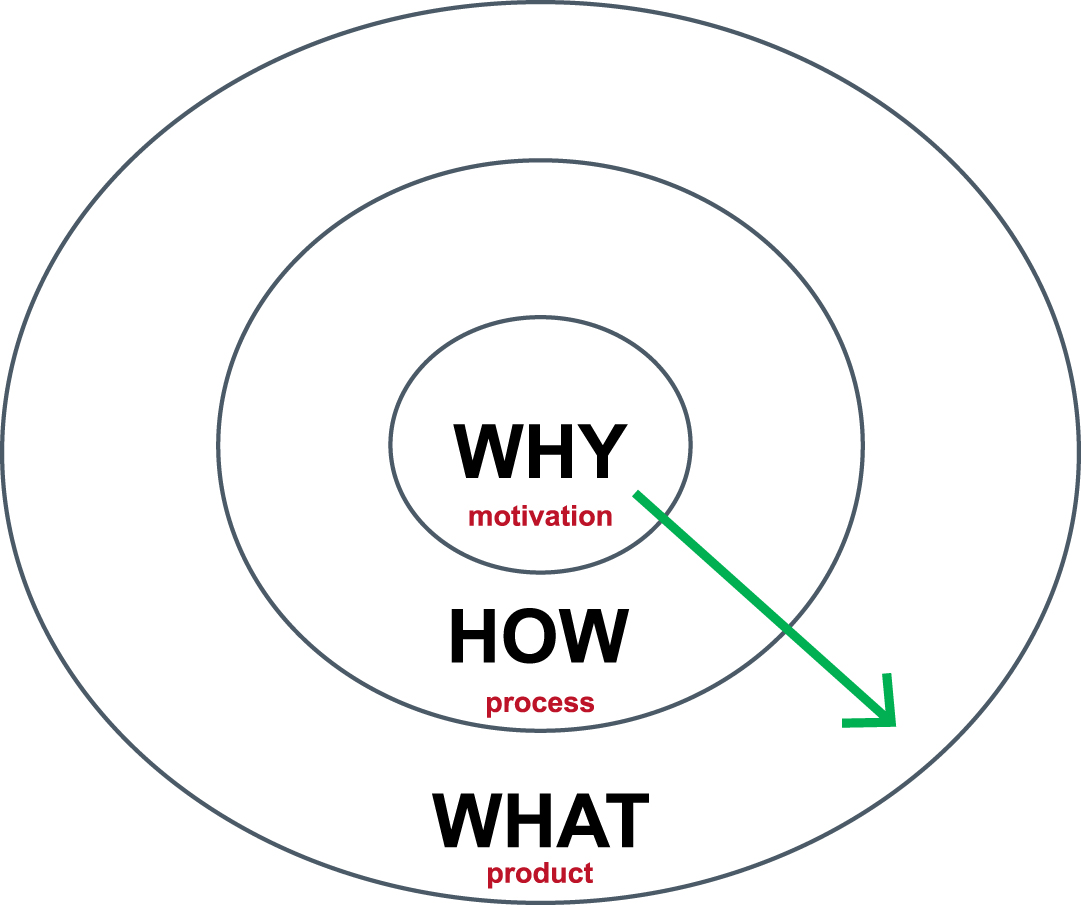

Ender, Alexander, and Joan show the same kind of critical thinking, but their way of thinking very untraditional. Simon Sinek, a motivational speaker and business consultant codified this pattern of thinking in what he calls “the golden circle” as shown in figure 1 (Sinek, 2009)

(Figure 1. The golden circle with order of communication)

Simon Sinek is given praise for his discovery; TED describes the concept of the golden circle as “a simple but powerful model for inspirational leadership” (Sinek Simon, 2009). There are three questions depicted in figure 1: what, how, and why. These can be described as follows: Every organization, and every leader knows what they do (Sinek, 2009). Most leaders know how they do what they do, but very few leaders know why they do what they do (Sinek, 2009). Why has nothing to do with victory on the battle field; why refers to cause, motivation, and belief of an individual leader. This concept explains why some leaders are able to inspire, whereas others aren’t. It is obvious that the average person communicates from the outside in, because they go from the clearest concept to the fuzziest. But according to Sinek, the inspired leaders regardless of their size, influence, or origin; all think, act, and communicate from the inside out of the golden circle (Sinek, 2009). For example, if Joan of Arc was an average leader, in a battle speech before a fight she may announce, “Follow me to victory! We will kill every Englishman in our path! We must take back our freedom!” This is following the golden circle but in the opposite direction to the arrow shown, i.e. going from what to why. But Joan of Arc was no average woman, she was considered a “mythological leader” (St. Joan of Arc Summary, n.d.). So in an actual war cry she likely said, “Believe in freedom for yourself, your family, and your country! Follow me without fear of the English weapons, and let our spears pierce their viscera! If you fight with courage, we will win this battle and every battle to come!” The latter speech is worded completely different, and more motivational. The only difference between the speeches was the order of following the golden circle. This is why Simon Sinek claims that most people do not buy what you do, but why you do it (Sinek, 2009).Those who start with why, have the capability of inspiring followers.

Our brain and the golden circle

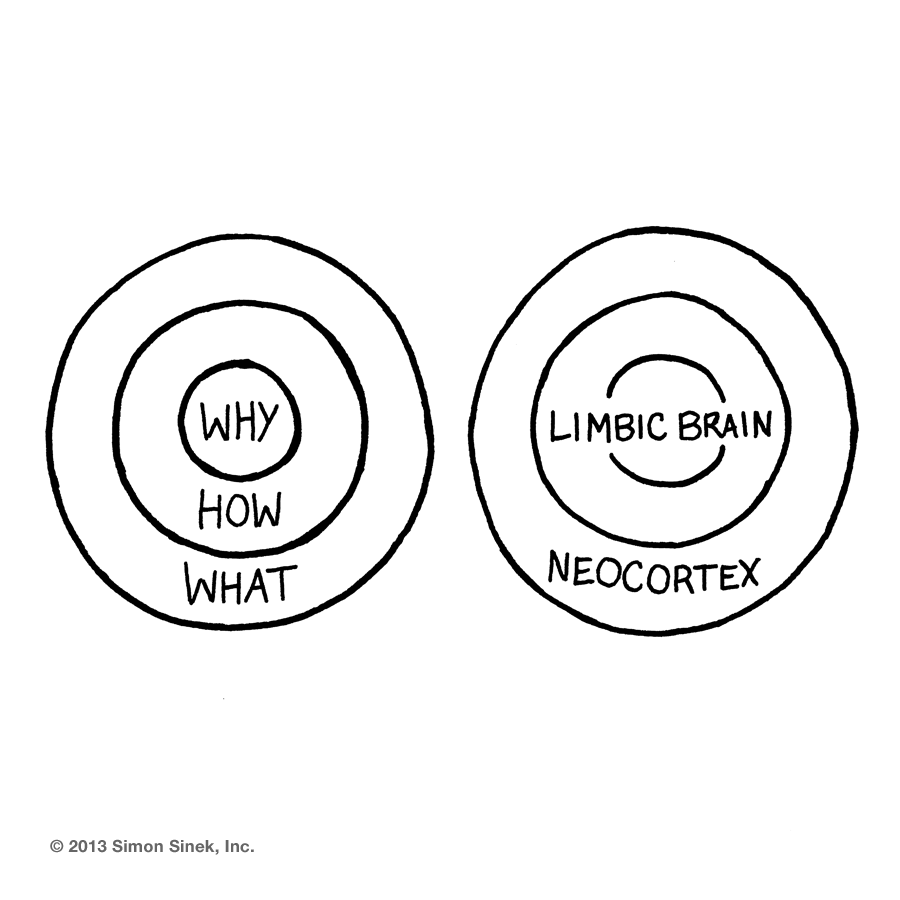

The best part of the golden circle is that it is not an opinion of Simon Sinek, but rather a consequence of brain biology. Looking at a cross section of the human brain, we see that the brain is divided into regions that correlate perfectly with the golden circle, as show in figure 2 (Start With Why,n.d.)

(Figure 2. How the brain and golden circle relate)

A firm reputation, military victories, and following the golden circle for communication are all the qualities of a great young leader. Whether Ender, Alexander the Great, or Joan of Arc, we follow those who lead because of the integrity, talent, and empathy young leaders present.

References

1. Borza, E. N. (2007). Alexander the Great: History and Cultural Politics. The Journal of the Historical Society, 441-442.

2. boscoanthony. (2013, January 9). The golden circle. Retrieved from Busniss Growth Strategist: http://www.boscoanthony.com/the-golden-circle/

3. Card, O. S. (1977). Ender's Game. New York: Tom Doherty Associates.

4. Freeman, J. (2008). Joan of Arc: Soldier, Saint, Symbol-of What? The Journal of Popular Culture, 601 - 634.

5. Reep, R. L., Finlay, B. L., & Darlington, R. B. (2007). The limbic system in mammalian brain evolution. Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 70(1), 57-70. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/docview/232161007?accountid=27203

6. St. Joan of Arc Summary. (n.d.). Retrieved from joanofarc.us: http://www.joanofarc.us/joan_of_arc_biography.html

7. Start With Why. (n.d.). Retrieved from LEAD: http://pssp.co.za/lead/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/golden-circle.jpg

8. Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. New York: Portfolio.

9. Sinek, Simon (September 2009). "How great leaders inspire action". TEDxPuget Sound. Retrieved 2015-01-05. 20,498,353 Total views

10. Kaas, J. H. (2005). The evolution of the neocortex from early mammals to modern humans. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(1), 11-14. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/docview/235186890?accountid=27203

background image:https://wordpress.org/support/topic/backgroundborder-only-going-halfway-down-page