Warhol's Critics

|

|

When Warhol hit his stride in the early sixties by appropriating images from advertising design and serializing them with a hands-off austerity, he became a lightening rod for criticism.

Studying the public perception of the artist in 1966, critic Lucy Lippard noticed that "Warhol's films and his art mean either nothing or a great deal. The choice is the viewer's. . . ." In retrospect, Lippard's early, tentative appraisal is revealing. While the images Warhol stumbled across have a deep resonance with the public, the problem of interpreting them is, depending one's point of view, simple or complex.

In the current polemic, Warhol's reputation

still depends on the reviewer's ideological or art-historical

preoccupations. If, as has been suggested, Warhol succeeded in redefining

the art experience, then the critical response required redefinition as well.

In retrospect, it appears that one problem that confronted critics and

journalists was that established critical approaches simply didn't lend

themselves to an art which they perceived as "artless, styleless, and

anonymous."

While the debate still hasn't resolved itself,

three interconnected issues figure prominently in the disagreements about

Warhol's reputation: his persona, his originality, and his antecedents.

Want to know more? Try these:

So why is Warhol the most controversial

artist of the century? Read on:

WARHOL'S PLACE IN MODERNISM

As a study of the criticism makes clear,

Warhol appalled the art establishment because he represented a complete

transvaluation of the aesthetic principles that had dominated for several

generations.

|

|

What for years modernists had deliberately ignored or contemptuously spurned, Warhol embraced. As appropriated mass-culture images—such as his Turquoise Marilyn (1962)—his "art" was indistinguishable from advertising—meaning it was crass and pedestrian—and thus lampooned the modern emphasis on noble sentiment and good taste. No doubt Warhol's comments about art, that it should be effortless, that it's a business having nothing to do with transcendence, truth, or sentiment, also infuriated detractors.

Both Warhol's subject matter and his flippant attitudes toward the conventions of the art world were the antithesis of the high-seriousness of modernism. And the rub of it was that his celebrations of the inconsequential were being taken seriously. It was a nasty slap in the face for those seeped in the myths of modernism.

Warhol's aesthetic contributed to the

breakdown of the hierarchial conventions of modernism, dissolving distinctions

between commercial design and serious art and the boundaries between popular

taste and high culture—or, as some would have it, between trash and excellence.

WARHOL AND POSTMODERNISM

|

|

As many observers now agree, the early 1960s mark the beginnings of a postmodern sensibility, where the modernist desire for closure and aesthetic autonomy has been rapidly replaced with indeterminacy and eclecticism.

If that's true, Warhol's art forecast and

then highlighted the changes that were occurring. And it has been argued that

his art anticipated many ploys of this aesthetic new world, including the

emphasis on irony, appropriation, and commonism, as well as promoting

intellectual engagement through negation.

SO WHAT'S WARHOL'S PLACE IN THE

CRITICISM?

"Criticism is so old fashioned. Why don't you just put in a lot of

gossip."

--Warhol to Bob Colacello, longtime editor of

Warhol's magazine Interview

In reviewing the critical record, one can conclude that Warhol's role in art

history is as a transitional figure. Stylistically his work is a

bellwether, and the critical issues raised about him often converge with those

at the center of the modern/postmodern debate. As a "mirror of the

times," Warhol criticism reflects the trepidation and enthusiasm in

response to shifting paradigms. Lucy Lippard's proposition is still

valid—Warhol's images are ambiguous. It's this ambiguity that gives his work

its edge. His images function as a sort of cultural Rorschach ink blot allowing

for the projection of personalities, theoretical orientations, and ideological

biases.

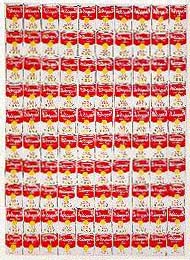

Why put fifty Cambell's soup cans on canvas? So far, there are scores of explanations. And the debate rages on....

For a complete discussion of Warhol's critics see The

Critical Response to Andy Warhol,

New York: Greenwood Press, 1997.

Return to Warhol | Return to Pratt